History of Vinton

THE EARLY YEARS OF THE TOWN

by Mark Hare

If one were to stand at the heart of Vinton and look back in time to 1886, the view would have been unrecognizable. It was still frontier country, uninhabited and untamed. That sense of being on the edge could be seen clearest if one traveled from the Sabine River to the east, following what was called the Old Spanish Trail, which was neither entirely old nor entirely Spanish but rather an Indian game trail adapted by the Spanish wandering north and south of what is now U.S. Hwy 90. The chief means of travel in the area relied on riverboats plying the Sabine and Calcasieu Rivers. Without bridges or roads capable of heavy traffic, much of the marsh land and bayous remained impassable. River travel made Lake Charles and settlement of the Parish possible, just as mining for sulfur led to the founding of Sulphur.

Various factors explain why Southwest Louisiana remained undeveloped until late in the 19th century. Geography was the first obvious hurdle. Much of southern Louisiana is delta marshland and bayou, prone to flooding, and the rich alluvial soil was too soft for stable roads in the age before asphalt and concrete. The remainder of the parish is prairie, which locals at the time thought useless for anything except grazing and generally avoided. For the same reason, settlement began in the east, where the alluvial soil attracted cotton and sugar cane farmers, and spread west. Compounding matters, no permanent bridge across the southern end of the Sabine existed until after the Civil War. Roads fared little better. There had been attempts to improve transportation, with little result. Confederate soldiers in 1863 cut a road extending from Niblett’s Bluff on the Sabine River to Alexandria, but it never developed into a major artery. A stagecoach route was established in 1869 from Niblett’s Bluff to New Iberia with an overnight stop in Lake Charles, an effort to improve mail service, but schooners continued to dominate the delivery of mail and heavy goods in Southwest Louisiana for decades.

Illustrative of the point is the pivotal Civil War battle at Niblett’s Bluff on the Sabine River just west of modern Vinton. Niblett’s Bluff was an important river port with a ferry and boat landing overlooking the only usable ford for miles. Union forces attempted to seize Niblett’s Bluff, first in 1863 through a failed river boat assault at Sabine Pass repulsed by Confederate artillery batteries and again in 1864 in a land assault from the north ending in retreat. The inability to capture Niblett’s Bluff prevented Union attempts to invade Southwest Louisiana and Texas throughout the war.

Politics also played a role in the lack of development in the region. From the beginning, the Spanish and French disputed the western boundary of Louisiana. Both sides monitored settlers in the region to make sure they possessed the proper grants from Spain or France, evicting those who did not belong. When America bought the territory, they inherited the dispute. In 1806, when border negotiations bogged down, the governments agreed to create a neutral strip or buffer zone where neither side would claim the land in question, referred to as the Rio Hondo Territory. Starting in 1810, both governments removed settlers in the Rio Hondo Territory, which included a sizable portion of modern Calcasieu Parish. Enforcement was largely haphazard and continued after Louisiana became a state in 1812. The area developed a legendary reputation as a lawless no man’s land, which persisted until the Adams-Onis Treaty, signed in 1819 and ratified in 1821, established a border. However, because of the Sabine River’s propensity to shift, the border remained the subject of lawsuits and disputes until well after the Civil War.

Despite the lack of development, pioneers had long been in the Vinton area. Jean Baptise Granger settled on acreage between what is now Vinton and Big Woods around 1827. Cattle, cotton, rice, fishing, and lumber formed the basis of economic life. A small but important trade in tobacco and indigo crops continued until sometime after the Civil War. Settlement on the western side of Calcasieu Parish did not begin in earnest until the 1880s.

The parish—and Vinton itself—might have remained a backwater if not for a confluence of events. The first event, which had the greatest material impact, was the decision by J. Pierpont Morgan’s Louisiana & Texas Railroad Company to construct a railroad from New Orleans to Beaumont, Texas. This line would become the present day Southern Pacific Railroad.

While it made great commercial sense to link major seacoast ports like Houston, Galveston, Beaumont, and New Orleans, the project flew against tradition, geography, and the existing road networks. While the Old Spanish Trail had been in intermittent use for more than a century – in Texas it becomes the Aisocita Road which ends in Goliad, with a branch turning north to San Antonio de Bexar – it was not the main road for commerce between Louisiana and Texas.

Until the 1880s, the most traveled—and oldest—route in use crossing the Sabine River was Domingo Ramón’s road, opened in 1716 with the intent to found new missions and presidios in East Texas. It ran from San Antonio to Nachitoches as part of the Camino Real network of trails, barely wide enough for a single oxcart, marked only by shallow ruts and rain-washed gullies, and notoriously hard to follow. Ramon’s road was a response to a French incursion in 1714, led by Louis Antoine Juchereau de St. Denis, to open a parallel road from Natchitoches, a city he helped to found, to San Antonio. More colorfully, when St. Denis reached the Rio Grande, his attempts to open trade between Louisiana and Mexico failed and resulted in his arrest, although he managed to fall in love with Manuela Sanchez, the daughter of a captain, and married her in 1715. St. Denis went on to serve as the guide for Ramon on his expedition, which founded six missions and a presidio on the new road. The expedition was hazardous, contending with Indians and the elements. Records show 82 horses died in crossing the Medina River alone. While some trade followed the Old Spanish trail in a route running from Galveston through southwest Louisiana to Opelousas and eventually New Orleans, most trade and travel tended to favor the northern route. It was not accidental that many of the early major cities in Texas and Louisiana appeared either along those northern routes or on the coast.

Timber changed everything. The part of Louisiana that included Calcasieu Parish was also home to the finest longleaf pine (pinus palustris) in the world. When combined with the stands of cypress and other hardwood lumber, logging was attractive and lucrative. The question was how to get to it. The numerous waterways throughout southwestern Louisiana made logging possible. While easy access to the lumber was one thing, hauling it by mule or ox teams proved a handicap because of the lack of roads and bridges. Logging was limited to within several hundred feet of the streams or rivers. By the mid-1880s, the depletion of the timber close to the waterways became a major concern. The solution was the introduction of narrow-gauge railroads for logging and transporting timber. Without railroads, the development of the area would have been impossible.

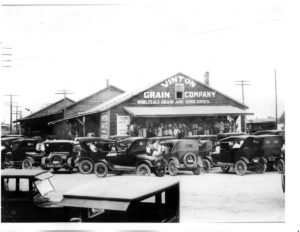

Growth accelerated as the railroads linked Louisiana to its neighbors. The railroad gave life to Lake Charles, Sulphur, and Vinton because it allowed the easy transportation of lumber, goods, and people to Beaumont, Galveston, and New Orleans, opening markets previously closed due to a lack of adequate roads. While shipping goods by sea remained cheaper than the railroads until the 20th century, railroads became a vital economic artery.

The logging industry held the status it did by 1886 because of one man, Daniel J. Goos, a former schooner captain who came to Lake Charles in 1855. There is some understandable confusion on his nationality. The Centennial History of Lake Charles incorrectly calls him a German immigrant from Schleswig-Holstein. During the 1850s, Schleswig-Holstein, much to the mutual irritation of the Germans and the Danes, was an independent duchy. The Danes annexed the duchy in 1863. In response, the Prussians won the province after a brutal little war in 1866. However, Goos may have been Dutch: he came from the Frisian Islands, a chain of barrier islands that extend along the northern coast of Holland to Denmark.

While Goos established one of the first sawmills west of New Orleans that was not his only contribution. In a pattern to be repeated thirty years later in Vinton, he brought with him a significant number of settlers from his native land. Hundreds, perhaps thousands came from Holland to Lake Charles in the decades after 1855, the majority of them from the island of Föhr, the home of Daniel Goos. German occupation, a lack of eligible bachelors on the islands, and economic reasons forced the move. There were enough Frisian settlers in Lake Charles to establish their own Lutheran Church in 1888. The influx of settlers solved another major problem hindering development: lack of manpower.

One important spur for the rapid changes during the 1880s was economic. The year 1886 saw the United States emerging from the third longest depression on record. Between 1883 and 1885 the financial and commercial markets suffered a severe downturn that peaked in the Panic of 1884. Thousands of people were out of work and many businesses and banks failed, driving people to seek better lives elsewhere. In response to the upheaval, the late 1880s and early 1890s saw the last great push for expansion to the west and south. Not until the Great Depression and dust bowl era would so many Americans pack up and move seeking new lives and fortunes elsewhere. Louisiana, like other states with virgin land for development, benefited.

Louisiana became attractive to settlers not just because of the land. The influx of Midwesterners, who recognized the value of the prairie areas for grazing, brought with them the cattle industry. Rice farming went from nonexistent to a major business starting around the time Vinton was founded. Sugar cane, previously lagging because of low prices, became viable during the 1890s.

A glance at population statistics shows how population ramped up: in the 1810 census Louisiana had 76,556 people and most of them lived along the Mississippi. By 1860 population rose to 708,002, still concentrated in the north and east. The population density jumped from 4 persons per square mile in 1850 to 21.5 in 1890 with the total population crossing a million. The statistics are also reflected in the many small towns appearing throughout Louisiana during the last quarter of the 19th century.

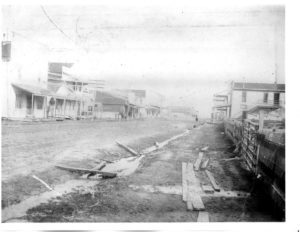

Among those small towns was Vinton. The settlement began with a switching track along the new railroad line. Although there would be a depot later, Vinton grew up around a whistle-stop called Blair. The source of the name is unknown. Some have speculated that the railroad siding took its name from a local family. However, no family named Blair was in residence in the area at that time. Another theory holds it was named after a railroad official, but no evidence exists to support the notion. At least one source holds the town was briefly called Morganstown after the J.P. Morgan railroad.

Dr. Seaman A. Knapp has a sizable if controversial place in the history of founding Vinton. Precisely what brought Dr. Knapp to Louisiana is unclear. Formerly the president of the Iowa Agricultural College in Ames, Dr. Knapp arrived in Lake Charles in 1884 and went to work running an agricultural business for land developer Jabez B. Watkins, the land magnate responsible for much of the growth of the area. Watkins was a native of Lawrence, Kansas who came to Lake Charles in 1883. Using English capital, Watkins bought 500,000 acres of prairie and marshland in Southwest Louisiana. To bring in settlers, he advertised in newspapers across the nation and attracted a heavy influx of people, especially to the Lake Charles area.

In 1887, Dr. Knapp quit his job with Watkins and opened his own land company. Some sources claim Dr. Knapp started his company in 1885, but the evidence is inconclusive. One possible reason Knapp started his own company lay in his lifelong campaign to modernize farming, the reason some believe he came to Louisiana. Local farmers resisted his innovations so Knapp began providing incentives for farmers to settle in townships under the condition they use his methods. Out of state settlers would be more likely to agree to such provisos, explaining Knapp’s interest in buying land and importing emigrants. Early accounts and secondary sources assumed Dr. Knapp was one of the settlers responding to the ads by Watkins and that Dr. Knapp was the leading force behind the first settlers in what would become the township of Vinton. This belief is reflected in recollections from the oldest Vinton residents and some newspaper accounts, which largely credit Dr. Knapp.

However, his true role in the development of Vinton remains uncertain due to contradictory evidence. The first purchases of land in the Vinton area began with someone else. On October 17, 1887 Robert F. Evans, an Iowa native, purchased 640 acres. More purchases followed under the names of Frank H. Banker and William Kirkman. The sources are unclear if the acreage was then sold to Dr. Knapp or Mr. George Horridge, who also bought large tracts of land across the parish starting in 1890. Records show that the Southern Real Estate and Guaranty Company bought all remaining land tracts within the future township by April 1889. The bulk of the land purchases date from 1890. The land was divided into lots and sold at prices ranging between 10 to 25 dollars each. In time, thirty blocks extended the original twelve-block plot of land. Records show Dr. Knapp and his partner purchased from the U.S. Government a combined 160-acre tract of land near Vinton in 1890. According to the survey plat, the three sections, number 17, 21, & 22, stretched west of Vinton parallel to modern I-10 and US 90. The land would later become farms, fitting in with Knapp’s original vision when he formed his real estate company. At the time, he paid $2.50 an acre. But that was land bought directly from the government; land bought from the Southern Real Estate Company for resell is another matter deserving further investigation.

The influx of settlers from Vinton, Iowa, formed the nucleus of the town. How many came because of Dr. Knapp is unknown. The Stevenson, Eddie, Ferguson, Stockwell, Morgan, Nelson, Fairchild, Banker, Hall, and Haskill families were Iowa transplants. Some streets bear the name of those families. When the post office was registered with the U.S. Postmaster General, Vinton was chosen as the name of the settlement.

Many assumed the name came from Dr. Knapp’s Iowa hometown, one reason he was credited with helping found the town. However, research by Alexander Colvin has shown a group of Vinton, Ohio natives sometimes wintered in the Lake Charles area dating back to the 1860s, calling themselves the Vinton Colony, adding further confusion to the picture. George Horridge was one of its members and was president of the colony. He eventually bought some 2,500 acres, including the bulk of what would become Horridge Street north of Hwy 90 in Vinton. It is possible George Horridge brought with him members of the Vinton Colony when he purchased land in the town, suggesting an alternative source for the town name.

The town grew rapidly. Right after the construction of the first homes came a sawmill, followed by the first public school. In 1890, Mrs. Mabel K. Kelly became the first teacher in Vinton. A larger school replaced the older structure in 1901. Senator Harrison C. Drew reorganized the Vinton Mill in 1893.

Churches always follow hard upon the founding of settlements. There is strong evidence the Methodist church in Vinton started at the same time as the town itself and may have offered the first organized services. However, much of the evidence is second-hand. No original sources remain. The committee that wrote the original history of the Vinton church in 1958 commented how the early years “was rich in legend and tradition” but steadfastly refused to give any details.

It is possible the settlers from Vinton, Iowa brought the church with them. There could have been a lay minister among the settlers, although the papers of the late R.M. Davis indicate that around 1888-1889 when Dr. John R. Miller, President Elder, came to Vinton he did not find an organized church. He noted Brother Gibson of Lake Arthur, who accompanied Dr. Miller, took charge of the Vinton church. At the same time, in a letter to Mrs. W.A. Sutton dated 31 July 1928, Reverend R.H. Wynn claimed that Brother R.P. Howell came to the area in May 1886 from Indian Bayou and preached in Vinton as part of his new pastorate, giving the first Methodist sermon in the community when he served as the pastor of the Sulphur Mines and Edgerly charge.

Church lore claims the congregation initially held their services in a local store and construction on a church building did not start until 1889. The church history noted young men without families served as stewards and other capacities in what was considered a mission station until 1900. Of the many lay persons and ministers to serve in Vinton, only the name of W. Schule has survived; no records remain of the others. Other churches would follow soon after, starting with the Catholic church.

At the same time Vinton was founded, a terrible hurricane struck near the mouth of the Sabine River on October 12, 1886, killing between 136 and 260 people. It would be the most destructive hurricane to hit the area until Audrey in 1957. Records suggest the storm was every bit as powerful as Audrey. Yet the event did little to stop the increasing influx of settlers.

Not even the extraordinary weather of 1895 made much impact. On February 14-15, 1895, the edge of the worst blizzard in American history touched southwestern Louisiana. The blizzard stretched from the Gulf Coast to New York, layering vast swathes of the country under snow drifts. Louisiana was not spared. A record 22 inches of snow fell on Lake Charles. Some areas reported snowfall between 18-24 inches. In Vinton, the cold crippled the new sheep industry and the farmers salvaged what they could by shaving wool from the dead flocks.

The final great spur to development in Southwest Louisiana made its appearance at the same time Vinton was founded and went unremarked upon. Although locals had recorded the location of petroleum springs along the Calcasieu River since 1839, no one thought of oil while drilling for sulfur in the early spring of 1886. No records tell of the reaction of the drilling crew when one mine struck oil instead of sulfur. The records do show that on March 25, 1886 at a depth of four hundred feet, a crew struck a pocket of oil, which yielded twenty-five barrels a day until the May 1887. When the well ran dry, the owners capped the site and everyone forgot about it until Spindletop ignited a new oil boom in 1901.

Oil changed the economic and demographic complexion of Texas and Louisiana when Captain Anthony Lucas struck oil at Spindletop on January 10, 1901. The results were astonishing. Beaumont grew from nine to fifty thousand people within a few weeks. When oil was found in Ged, not far from Vinton, it had a similar if lesser effect. The Vinton dome, some four miles to the southwest of the town, one of thirty-six such domes recorded before 1911, was discovered in 1901 but did not produce oil until 1910. At its height, some 1200 oil wells were drilled into the field.

Census data shows the town grew rapidly once incorporated, perhaps stimulated by the growing rice, sugar cane, cattle, and oil industries. In 1900, the population in Vinton numbered sixty-two people. The 1920 census listed a population of 1,441. By 1930 the number reached 1,989. The Great Depression led to a population drop by 1940 and Vinton did not recover until the 1950s when it saw another growth spurt in the post-World War 2 boom era.

During the early years, the town grew in other ways. The Vinton Literary Club founded the Vinton Library Club, the first free public library in Vinton, in 1919 through the efforts of Mrs. W.E. (Lina) Lundy and other women. The library originally hosted some 35 volumes in the back of a local store owned by Miss M. Carter and later moved to a larger room that formerly held the Delure Studio.

Calcasieu Parish lacked an organized library system until Sallie Farrell, a field worker for the State Library Commission, organized a parish-wide service at the Lake Charles courthouse on January 22, 1944. A branch library opened in Sulphur in April of that year on the site of the old LeBlanc café on W. Napoleon. Dixie Traver was the first librarian. At this same time, the Vinton Library Club sold its collection to the Parish and the new Vinton Branch of the Calcasieu Parish Library System opened on April 18, 1944. In 1961, the library moved to its present location next to the City Park and renamed in honor of Jimmy Lee Fontenot, a former member of the Police Jury from 1948 to 1962.

In February 1915, Gustave “Gus” Courrege opened the Vinton Blacksmith Shop and Rice Mill on Hampton Street, which remained open until his death. The structure was demolished in 2000. Gustave Couregge was more than a blacksmith. He joined the Vinton Bucket Brigade in 1911 at the age of 17 and became the Vinton Fire Chief in 1916, a position he would hold until named Town Fire Marshall in 1962. Before the Town bought its first mechanical pumper truck in the 1928, Gus towed the fire tank to fires using his own horse and buggy. He was on hand for one of the worst fires in Vinton history, when the entire 1200 block of main street went up in flames, resulting in the total loss of all businesses and homes.

Until 1910, Vinton was officially a village. After a special election, Governor Jared Y. Sanders appointed Alexander Perry as the first Mayor and incorporated the Town of Vinton by proclamation on October 10, 1910. Mr. Perry served as Mayor until July 1, 1911. Walter Perry also served as the first official town marshal. That same year, a new mayor and council of aldermen were chosen in another election.